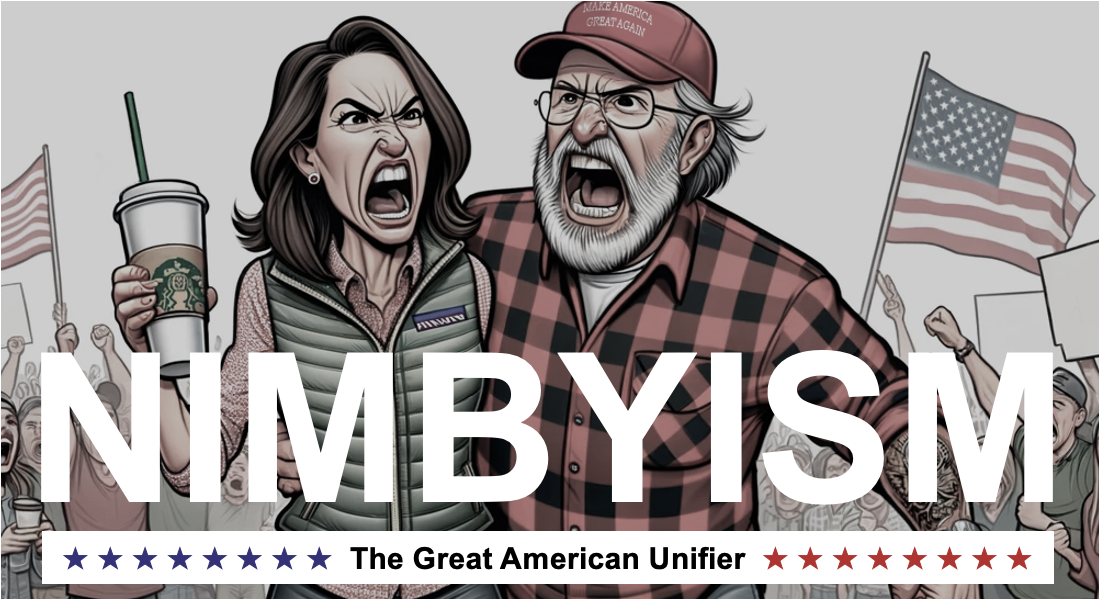

Democrats and Republicans disagree about (almost*) everything...

...and they increasingly hate each other.

...but Republicans and Democrats often unite in their opposition to development.

A developer pitches a housing project in Tuscaloosa, but the council voted against the proposal after a line of protestors argued against growth.

"The people who moved over the spillway did so to get away from commercial development. The people do not want asphalt, we do not want neon signs and we do not want streetlights.”

The playbook against developers (and growth) is consistent for Republicans and Democrats, alike, with a focus on fears over density, traffic, and/or renters.

Example 1: The Bronx, New York

The Bronx sent the NYC City Council its first Republican councilmember in 40 years, in large part due to the incumbent's vote in support of a housing development.

How did the Bronx get its first Republican representative in 40 years?

From Hellgate NYC (Nov. 8, 2023):

Republican Kristy Marmorato defeated incumbent City Councilmember Marjorie Velázquez in the Bronx by just 708 votes, thanks to Marmorato's campaign that was almost entirely based on opposing the Bruckner Boulevard rezoning and the hundreds of apartments (many for veterans and seniors) that are now going up as a result. Velázquez was initially against the project, then was for it, but it was too late—Marmorato mobilized just enough NIMBY East Bronx homeowners and now she'll be the first Republican to represent the Bronx since 1983.

Source: NY TImes

From New York Magazine Intelligencer (Nov. 11, 2023):

The surprising defeat of City Councilwoman Marjorie Velázquez in Tuesday’s elections is a loss that hurts all of New York, affecting people who have never visited the 13th District in the northeast Bronx. In a part of the city that usually votes Democratic, a first-time Republican candidate named Kristy Marmorato, an X-ray technician, pulled off the unlikely feat of dispatching an incumbent, winning 53 percent of the vote in a district with a nearly 62 percent Democratic enrollment.

The move that doomed Velázquez politically was her vote for last year’s rezoning of Bruckner Boulevard, a measure approved by a vote of the full council that will create a few hundred much-needed apartments in a city that is desperate for housing.

The proposal itself is a simple, sensible, and modest change in zoning to allow four buildings to go up, two of them eight stories high, at 2945 Bruckner Boulevard. Nearly half of the 350 apartments scheduled to be built will be rent stabilized with 99 set aside for seniors and 22 for veterans, along with a new supermarket and community meeting space.

Example 2: Marin County, California

Marin County in Northern California has historically leaned strongly Democratic.

The owner of this 80-year-old seminary in Northern California has been trying to get the site rezoned for about 10 years.

The proposed redevelopment would include apartments, low-density rentals, student housing, senior housing, retail, and a fitness center.

Long-time Marin resident speaker at City Council meeting:

Community input that has been received has been ignored. And a narrow, self-serving focus on what is best for the landowner not the community at large has prevailed . North Coast [land owner] has had plenty of time to prepare an appropriate proposal but but it continues stubbornly to present the same non-conforming proposal again and again. For these reasons I ask that you deny their request.

We don't want apartments or traffic!

Plano is in Collin County, which has historically leaned strongly Republican.

Source: D Magazine

From D Magazine (Aug. 4, 2020):

The final death knell for one of the most promising, forward-thinking urban planning efforts in North Texas will will be sounded tomorrow. During a joint session of the city of Plano’s City Council and Planning and Zoning Commission, Plano officials are expected to vote to repeal the city’s Plano Tomorrow Comprehensive Plan and replace it with the 1986 master plan—literally putting Plano a generation behind on planning for its future growth and success.

The Plano Tomorrow Comprehensive Plan was adopted in 2015, and since then, it has been embroiled in a long legal feud seeking its repeal. Opponents feared the new plan and said it would allow dangerous amounts of density that would erode the suburban city’s character. To me, the Plano Tomorrow plan looked like exactly the kind of urban planning vision that could begin to reverse the damaging effects of 70 years of sprawl-style suburban growth.

That style of growth, while often trumpeted as the bedrock of the region’s incredible economic success, has also proven to treat North Texas cities and communities like disposable commodities, cycling urban neighborhoods and inner-ring suburbs alike through a series of booms and busts. The short-term economic gains of sprawl-style growth do not pay for the ultimate erosion of tax bases, inequitable transfers of wealth, and hidden costs of living.

Plano was once the poster child of sprawl, which made the Plano Tomorrow plan even more extraordinary and revolutionary. The plan recognized that the pattern of growth that has defined the last 70 years of urban expansion in North Texas will not allow the region to remain sustainable, and it charted a new path forward. It allowed for pockets of density, rethought how to integrate transit into a highway-dominated city, and accommodated for a deepening tax base driven by a mix of commercial and residential investment. It reimagined the suburban city not as a commuter-berg of single-family houses flanked by highways and strip centers, but as a vibrant, resilient community unto itself.

Plano Tomorrow wasn’t perfect, but it recognized reality: more than a half-century of economic growth has transformed Plano from an ideal suburban utopia into a more dynamic and complex city, with large job centers, an expanding commercial base, and demand for a diversity of housing, services, and mobility options. But that was too much for some Plano residents. They fought the adoption of the plan through the courts while waging a disinformation campaign that drudged up tired clichés about density and urban life.

These attacks represented parochial NIMBYism at best, and thinly veiled endemic racism at worst. The anti-Plano Tomorrow crowd often repeated erroneous claims that the master plan would overcrowd schools and allow “high density, multi-family residential development on every-four corner intersection,” as the Dallas Morning News reports. Another Plano resident once accused Plano Mayor Harry LaRosiliere of trying to turn “Plano into Harlem.”

Watch NIMBY fight breaking out in Plano here.

Our takeaways

Real estate developers are proving that liberals and conservatives can agree on something: A shared desire to hinder development.

Despite rumblings about how NIMBYism is counterproductive, not-in-my-backyard activism shows no signs of abating, which creates several problems for communities...

- Hypocrisy: Many communities that vigorously undermine new development are defined by transplants. i.e., "I just moved here from XYZ and want to protect my community."

- Undermined growth plans: Most cities have adopted formal "master plans," but can those be strategically implemented when new development community groups undermine new projects?

- Limited shared benefits: Developers build because they think they can deliver profitable projects; e.g., assume a developer thinks she can build a project with $3M of annual NOI to a 6% yield-on-cost and sell it at a 5% exit cap rate. That's $10M in anticipated profit. Beating up developers instead of working with them incentivizes them to hide the ball, play politics, and fish for relatively favorable municipalities/city leaders. Working with them could lead to generating additional revenue and value for communities and taxpayers, which could help schools, roads, etc.

- Stops (or at least slows) growth: Despite being political opposites, Plano, the Bronx, and Marin County have a lot in common when it comes to development; they don't want it. This evolving attitude permeates all levels of local government and creates significant walls that must be climbed for developments to break ground. Hearing a nearby homeowner complain about traffic may be more appealing than talking about lost tax dollars, but development is a primary engine of the revenue that fuels growing cities.

- Concentrated power: When community responses to development plans are defined by the loudest voices in the room (typically nearby owners who are opposed to all growth), decision-making often gets concentrated in the hands of a select few officials. This dynamic exacerbates the problems outlined above and often leaves very few winners (except for the developer and the swing/influential vote.)

COMMENTS