So you want to invest in distress? History's lessons...

"Grave dancing is an art that has many potential benefits. But one must be careful while prancing around not to fall into the open pit and join the cadaver. There is often a thin line between the dancer and the danced upon."

Distress investing sounds great in hindsight—who doesn’t want to buy low and sell high? But the devil is in the details.

---- Case study ----

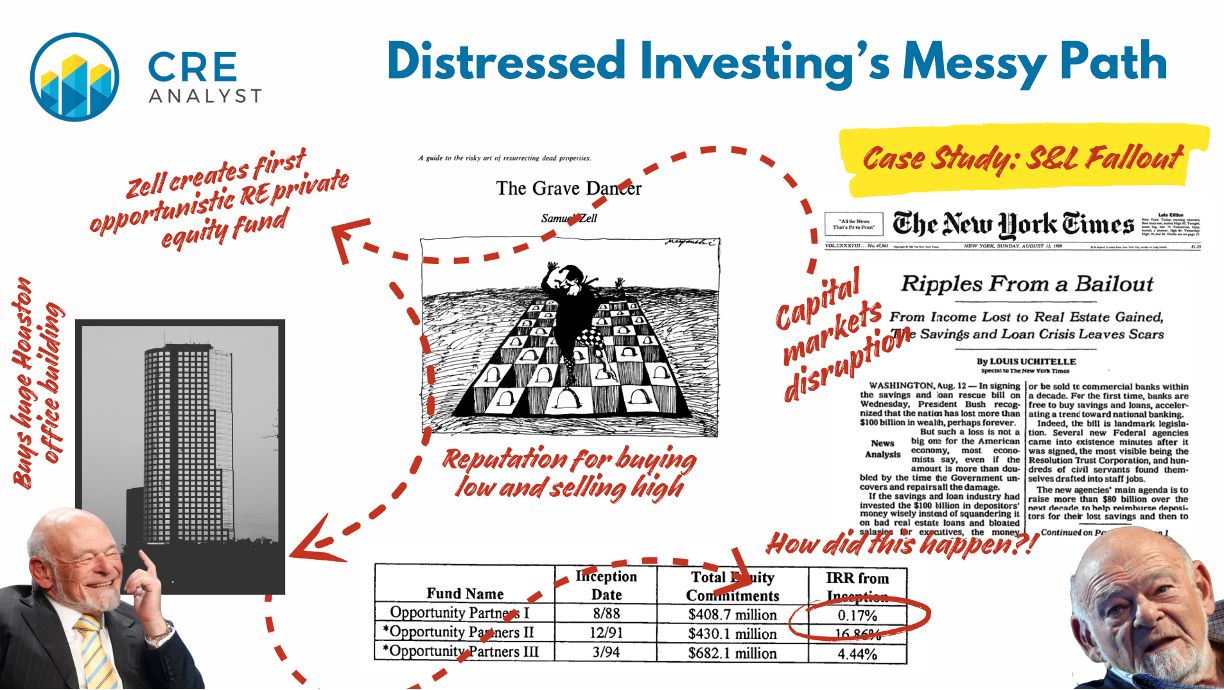

Sam Zell and the first REPE Fund...

Narrative:

Zell was legendary for capitalizing on overleveraged owners and shaky underwriting. He swooped in when others panicked, buying assets for pennies on the dollar and flipping them into a billion-dollar empire. He was the master of buying low and selling high.

Reality:

Zell didn’t just inherit the "Grave Dancer" moniker—he gave it to himself in a 1976 article outlining his approach to distressed deals. And for much of his career, it worked. He bought cheap, stabilized, and sold high—often to the public markets.

But when the real estate capital markets collapsed after the S&L crisis in the late 80s, even Zell faced a harsh reality: He needed capital, and it wasn’t available.

To take advantage of the downturn, he spent months traveling the country with Merrill Lynch, raising $400M for what would become the first-ever opportunistic real estate fund. Investors gave him full discretion—as long as he exited within 7-10 years.

His biggest early move? Rolling a 1986 deal—San Felipe Plaza in Houston—into the fund. He had acquired it for $135M and believed it would be a profitable long-term play. He was right and would eventually sell the asset for $280M.

...but hindsight narratives almost always ignore some not-so-sexy nuances:

-- The building was quickly written down by $20M.

-- Zell eventually recognized a big gain, but it wasn't until 20 years later, more than 2x the expected hold period of the fund. Timing matters.

-- By the time the first opportunistic fund wound down, its IRR was just 0.17%.

---- Bigger picture ----

All's well that ends well?

Despite that early fund’s rough outcome, Zell kept raising capital and refining his model. His Opportunity Partners series laid the foundation for Equity Office Properties, which he later took public. Then in 2007 he sold it to Blackstone in the largest LBO in history (at the time).

---- Uncertainty cuts both ways ----

In 1991, Salomon Brothers predicted it would take decades for real estate to recover from the S&L crisis.

-- Boston: 26 years

-- New York: 46 years

-- San Antonio: 56 years

Like Zell, they were also wrong. Recovery looked impossible through a lens defined by overhang and minimal activity.

---- Takeaways ----

1. Distress investing isn’t about seeing the pain—it’s about knowing when the pain ends.

2. Directional ideas are worthless without execution.

3. Liquidity and timing often define outcomes.

History's lesson for distressed real estate investors: Be careful.

COMMENTS